Section II: Evidence-based Opioid Prevention Interventions

Prevention interventions can take many forms—ranging from large, statewide campaigns to focused interventions for specific individuals or populations. This section presents four strategy “categories” that have evidence of effectiveness, and that local boards of health can implement to reduce opioid misuse and overdose.[1] Links to additional information on these strategies is included in Section V: Resources

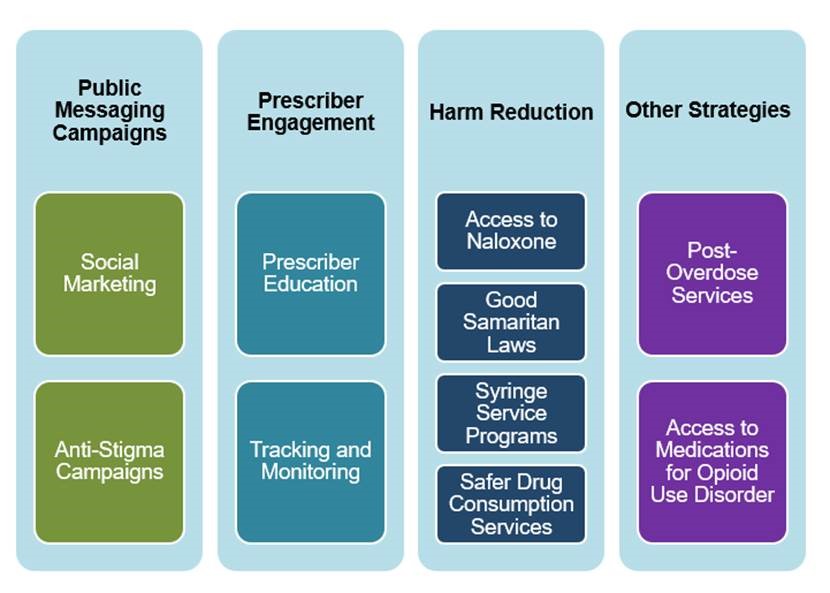

Opioid Prevention Strategies at a Glance

Public Messaging Campaigns

Public messaging campaigns are often used to raise awareness about a specific health issue or create the conditions necessary for behavioral change.

But not all messages are created equal. Research has shown that campaigns that paint drug misuse as simply the wrong thing to do—such as the “Just Say No” campaign of the 1980s—do not work. Instead, effective public messaging tries to educate and inform people, rather than rely heavily on scare tactics or fear-based messaging.

We also know that design and implementation matters. According to the research, public health communications campaigns are most likely to be effective when they:

- Are part of a more comprehensive prevention campaign.

- Present clear messaging and action steps.

- Deliver the right message to the right audience through the right channels.

Social marketing. Many public messaging campaigns use social marketing, an approach adapted from commercial marketing, to encourage favorable and voluntary behavior change. Social marketing messages reinforce the benefits of engaging in a specific behavior while

minimizing the perceived negative consequences typically associated with behavior change.

Campaigns can take different forms:

- Some social marketing campaigns target factors that contribute to opioid misuse, such as those that focus on storing opioids safely.

- Other campaigns seek to improve responses to overdoses, for example, by providing

information on relevant Good Samaritan Laws that protect from drug-related criminal charges those individuals who report an overdose to emergency medical personnel.

Anti-stigma campaigns. An important priority when working to reduce opioid misuse is to reshape attitudes and reduce the stigma that prevents many individuals from accessing the care they need. Like people struggling with other chronic diseases, people with OUD deserve respect and support.

Prescriber Education

Since prescription opioids can be highly addictive, working directly with opioid prescribers on misuse prevention is imperative. There are several ways to do this:

Prescriber education programs. The goal of prescriber education programs is to make sure that prescribers are using safe practices to help their patients manage their physical pain without becoming addicted to opioids. Prescriber education involves teaching prescribers about the benefits and risks of prescribing opioids, including strategies to prevent misuse, while maintaining legitimate and appropriate access to opioids for patients. Topics for prescriber education may include the following:

- Best practices for when and how to prescribe opioids or other drugs with abuse potential

- How to recognize when an individual is at risk for opioid misuse or an overdose

- When and how to refer individuals to treatment services

- How to talk with patients about the dangers of prescription drug overdoses

- Information on other strategies to prevent overdoses

Prescriber education may be delivered through a variety of venues, including:

- Events sponsored by drug manufacturers

- Continuing medical education programs

- State-mandated training events, delivered in partnership with local boards of health

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has provided guidelines for prescribing opioids[1] for chronic pain which prevention practitioners can use to guide the creation of educational materials. Experience dictates, however, that prescriber education is best received when the individual delivering the educational message is another prescriber (i.e., a physician) or someone with medical credentials.

Tracking and monitoring strategies. Tracking and monitoring is an important component of preventing overdose. A key resource in this task is Massachusetts’ Prescription Monitoring Programs (PMP)—a statewide electronic database that collects, analyzes, and makes available prescription data on controlled substances dispensed by non-hospital pharmacies and practitioners.

- The purpose of the PMP is to prevent individuals from receiving medically unnecessary prescriptions, knowingly or not, that may be misused or cause overdoses.

- State law requires that all Massachusetts prescribers query the PMP, using the Massachusetts Prescription Awareness Tool (MassPAT), before prescribing a Schedule II or III narcotic medication or a benzodiazepine.

Health departments can use PMP data in a variety of ways to address the prescription drug and opioid epidemics, making them key public health and safety tools. You can use these data to identify and/or refine priorities, and to focus prevention efforts. You can also use PMP data to change prescriber behavior. For example, many states share PMP data using prescriber “report cards,” which compare practitioners’ prescribing practices to their peers in the same specialty. These reports can alert prescribers about at-risk patients and prompt them to take necessary steps to prevent opioid misuse.

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction programs provide essential health information and services while respecting individual dignity and autonomy. For individuals who use drugs, harm reduction recognizes that many individuals who use drugs are either unable to stop or are not ready for treatment at a given time.

Harm reduction programs focus on limiting the risks and harms associated with unsafe drug use rather than promoting abstinence. Harm reduction efforts have been shown to play a key role in reducing serious health consequences associated with substance misuse, including HIV transmission, viral hepatitis, and death from overdose.

Harm reduction strategies often entail the enactment of policies that provide access to life-saving antidotes (such as naloxone), implemented in conjunction with other efforts to reduce non-fatal overdose, such as overdose education. Many of these policies, such as Good Samaritan Laws, also protect against legal repercussions of use.

Access to Naloxone. Naloxone, commonly sold under the brand names Narcan and Evzio, are opioid antagonists—medications that block the body’s opioid receptors to prevent interactions with opioid drugs. This blockage can halt an overdose before potentially fatal symptoms, such as respiratory depression, take full effect. Many communities receive Federal funding to distribute naloxone through grants such as the First Responders-Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act.

- Massachusetts DPH has issued a statewide standing order that allows retail pharmacies to dispense naloxone without a prescription. It dictates that all Massachusetts retail pharmacies licensed by the Board of Pharmacy maintain a continuous, sufficient supply of naloxone rescue kits. Customers can pay at the time of purchase, or their insurance will be billed.

911 Good Samaritan Laws. The Massachusetts Good Samaritan Law (“Immunity from prosecution under Secs. 34A for persons seeking medical assistance for self or other experiencing a drug-related overdose”) provides legal protections for individuals who call for emergency assistance (such as 9-1-1) in the event of a drug overdose. It may also protect individuals from arrest and/or prosecution for crimes related to drug possession, drug paraphernalia possession, and other crimes.

By providing these protections, this law has significant potential to help reduce the impact of the opioid epidemic by encouraging people to summon emergency assistance if they experience or witness a drug overdose.

Syringe Service Programs. Syringe service programs (SSPs), also known as needle exchange programs, provide people who use injection drugs with access to sterile injection equipment and syringe disposal services free of cost. They also provide referrals to other services such as testing for hepatitis C, HIV, and other sexually transmitted diseases, substance use disorder treatment, risk reduction counseling, and naloxone.

- SSPs have been associated with increased entry into substance use disorder treatment programs, decreased overdose deaths, reduction in needle stick injuries for first responders and the general public, decreases in new HIV and viral hepatitis infections, and savings in health care dollars by focusing on primary prevention.

- As of July 1, 2016, the local board of health in any Massachusetts city or town may approve the establishment of an SSP in that city or town. There are currently 10 needle exchanges in Massachusetts, and 41 communities currently have approval to establish programs.

Safer Drug Consumption Services. These services aim to reduce health risks among people who use drugs as well as public substance use and related problems within the broader community. People can obtain sterile injection equipment for use on site, and facilities are equipped with naloxone and staffed by individuals who are trained to recognize and respond effectively to an overdose. People who use these services also receive individualized information about their substance use-related risks and safer use practices. Safer drug consumption services have been successful in reaching the most marginalized populations of people who use drugs, who are least likely to obtain access to medical and social support, and connect them with health and social services.

Other Strategies

Post-Overdose Interventions. Despite public messaging campaigns, prescriber education efforts, and the implementation of harm reduction strategies, opioid overdoses will still occur—and people who survive an overdose are at increased risk of dying from another one. This is why programs to support individuals who have survived an opioid overdose are also an important part of prevention. Post-overdose interventions have shown promise in reducing the risk of subsequent overdoses and improving other health outcomes among people who have experienced a non-fatal overdose. These programs are based on some key principles, including establishing positive relationships with survivors and helping survivors navigate social services systems.

Sometimes referred to as warm handoffs, these interventions represent a collaborative effort among law enforcement, medical providers, social workers, and prevention professionals to engage individuals who have experienced a non-fatal overdose and their family members in the period immediately following the overdose event.

Access to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. For people with OUD/SUD, having access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) can be one part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce overdose. MOUD involves integrating medications (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) with behavioral therapies and counseling to treat opioid addiction. Research demonstrates that MOUD has been effective in helping people recover, as well as in reducing instances of overdose.

In 2020, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recommended replacing the term Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) with MOUD. MAT implies that medication plays a secondary role to other approaches, while MOUD reinforces the idea that medication is its own treatment form.

[2] CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control is in the process of updating the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. The anticipated release of the new guidelines is late 2022.